Executive Summary

- The most useful summary statistic for a trended variable is the average growth rate

- But there are several different methods for calculating average growth rates that can often generate very different results depending on whether all the data is used or just the start and end points, and whether simple or compound growth is assumed

- Be careful of calculating average growth rates using only the start and end points of trended variables since this implicitly assumes that these two points are representative of the dynamic path of the trended variable and may give a very biased estimate of the underlying growth rate

- Best practice is to use all of the available data to estimate a loglinear trendline which allows for compound growth and avoids having to calculate an appropriate midpoint of a linear trendline to convert the estimated slope into growth rate

When providing summary statistics for trended time-series data, the mean makes no sense as a measure of the point of central tendency. By definition, there is no point of central tendency in trended data. Trended data are either increasing or decreasing in which case the most useful summary statistic is the average rate of growth/decline. But how do you calculate the average growth rate? In this post I want to discuss the pros and cons of the different ways of calculating the average growth rate, using total league attendances in English football (the subject of my previous post) as an illustration.

There are at least five different methods of calculating the average growth rate:

- “Averaged” growth rate: use gt = (yt – yt-1)/yt-1 to calculate the growth rate for each period then average these growth rates

- Simple growth rate: use the start and end values of the trended variable to calculate the simple growth rate with the trended variable modelled as yt+n = yt(1 + ng)

- Compound growth rate: use the start and end values of the trended variable to calculate the compound growth rate with the trended variable modelled as yt+n = yt(1 + g)n

- Linear trendline: estimate the line of best fit for yt = a + gt (i.e. simple growth)

- Loglinear trendline: estimate the line of best fit for ln yt = a + gt (i.e. compound growth)

where y = the trended variable; g = growth rate; t = time period; n = number of time periods; a = intercept in line of best fit

These methods differ in two ways. First, they differ as to whether the trend is modelled as simple growth (Methods 2, 4) or compound growth (Methods 3, 5). Method 1 is effectively neutral in this respect. Second, the methods differ in terms of whether they use only the start and end points of the trended variable (Methods 2, 3) or use all of the available data (Methods 1, 4, 5). The problem with only using the start and end points is that there is an implicit assumption that these are representative of the underlying trend with relatively little “noise”. But this is not always the case and there is a real possibility of these methods biasing the average growth rate upwards or downwards as illustrated by the following analysis of the trends in football league attendances in England since the end of the Second World War.

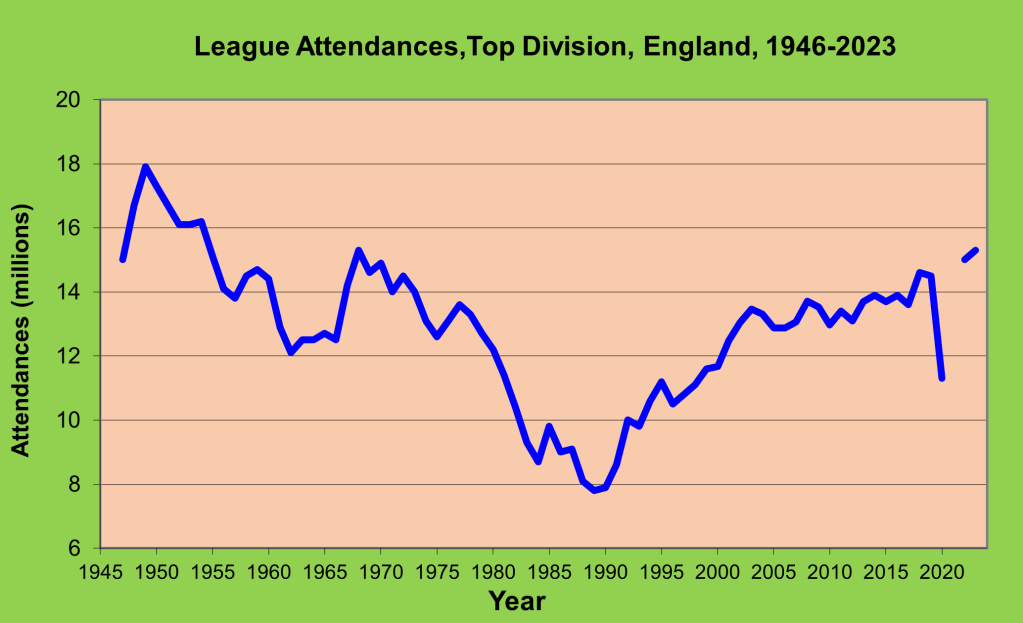

Figure 1: Total League Attendances (Regular Season), England, 1946/47-2022/23

This U-shaped timeplot of total league attendances in England since the end of the Second World War splits into two distinct sub-periods of decline/growth:

- Postwar decline: 1948/49 – 1985/86

- Current revival: 1985/86 – 2022/23

Applying the five methods to calculate the average annual growth rate of these two sub-periods yields the following results:

| Method | Postwar Decline 1948/49 – 1985/86 | Current Revival 1985/86 – 2022/23* |

| Method 1: “averaged” growth rate | -2.36% | 2.28% |

| Method 2: simple growth rate | -1.62% | 3.00% |

| Method 3: compound growth | -2.45% | 2.04% |

| Method 4: linear trendline | -1.89% | 1.75% |

| Method 5: loglinear trendline | -1.95% | 1.85% |

What the results show very clearly is the wide variability in the estimates of average annual growth rates depending on the method of calculation. The average annual rate of decline in league attendances between 1949 and 1986 varies between -1.62% (Method 2 – simple growth rate) to -2.45% (Method 3 – compound growth rate). Similarly the average annual rate of growth from 1986 onwards ranges from 1.75% (Method 4 – linear trendline) to 3.00% (Method 2 – simple growth rate). To investigate exactly why the two alternative methods for calculating the simple growth rate during the Current Revival give such different results, the linear trendline for 1985/86 – 2022/23 is shown graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Linear Trendline, Total League Attendances, England, 1985/86 – 2022/23

As can be seen, the linear trendline has a high goodness of fit (R2 = 93.1%) and the fitted endpoint is very close to the actual gate attendance of 34.8 million in 2022/23. However, there is a relatively large divergence at the start of the period with the fitted trendline having a value of 18.2 million whereas the actual gate attendance in 1985/86 was 16.5 million. It is this divergence that accounts in part for the very different estimates of average annual growth rate generated by the two methods despite both assuming a simple growth rate model. (The rest of the divergence is due to the use of midpoint to convert the slope of the trendline into a growth rate.)

So which method should be used? My advice is to be very wary of calculating average growth rates using only the start and end points of trended variables. You are implicitly assuming that these two points are representative of the dynamic path of the trended variable and may give a very biased estimate of the underlying growth rate. My preference is always to use all of the available data to estimate a loglinear trendline which allows for compound growth and avoids having to calculate an appropriate midpoint of a linear trendline to convert the estimated slope into a growth rate.

Read Other Related Posts