Executive Summary

- Context is crucial in data analytics because the purpose of data analytics is always practical to improve future performance

- The context of a decision is the totality of the conditions that constitute the circumstances of the specific decision

- The three key characteristics of the context of human behaviour in a social setting are (i) uniqueness; (ii) “infinitiveness”; and (iii) uncertainty

- There are five inter-related implications for data analysts if they accept the critical importance of context:

Implication 1: The need to recognise that datasets and analytical models are always human-created “realisations” of the real world.

Implication 2: All datasets and analytical models are de-contextualised abstractions.

Implication 3: Data analytics should seek to generalise from a sample rather than testing the validity of universal hypotheses.

Implication 4: Given that every observation in a dataset is unique in its context, it is vital that exploratory data analysis investigates whether or not a dataset fulfils the similarity and variability requirements for valid analytical investigation.

Implication 5: It is misleading to consider analytical models as comprising dependent and independent variable

As discussed in a previous post, “What is data analytics?” (11th Sept 2023), data analytics is best defined as data analysis for practical purpose. The role of data analytics is to use data analysis to provide an evidential basis for managers to make evidence-based decisions on the most effective intervention to improve performance. Academics do not typically do data analytics since they are mostly using empirical analysis to pursue disciplinary, not practical, purposes. As soon as you move from disciplinary purpose to practical purpose, then context becomes crucial. In this post I want to explore the implications for data analytics of the importance of context.

The principal role of management is to maintain and improve the performance levels of the people and resources for which they are responsible. Managers are constantly making decisions on how to intervene and take action to improve performance. To be effective, these decisions must be appropriate given the specific circumstances that prevail. This is what I call the “context” of the decision – the totality of the conditions that constitute the circumstances of the specific decision.

In the case of human behaviour in a social setting, there are three key characteristics of the context:

- Unique

Every context is unique. As Heraclitus famously remarked, “You can never step into the same river twice”. You as an individual will have changed by the time that you next step into the river, and the river itself will also have changed – you will not be stepping into the same water in the exactly the same place. So too with any decision context; however similar to previous decision contexts, there will some unique features including of course that the decision-maker will have experience of the decision from the previous occasion. In life, change is the only constant. From this perspective, there can never be universality in the sense of prescriptions on what to do for any particular type of decision irrespective of the specifics of the particular context. A decision is always context-specific and the context is always unique.

2. “Infinitive”

By “infinitive” I mean that there are an infinite number of possible aspects of any given decision situation. There is no definitive set of descriptors that can capture fully the totality of the context of a specific decision.

3. Uncertainty

All human behaviour occurs in the context of uncertainty. We can never fully understand the past which will always remain contestable to some extent with the possibility of alternative explanations and interpretations. And we can never know in advance the full consequences of our decisions and actions because the future is unknowable. Treating the past and future as certain or probabilistic disguises but does not remove uncertainty. Human knowledge is always partial and fallible

Much of the failings of data analytics derive from ignoring the uniqueness, “infinitiveness” and uncertainty of decision situations. I often describe it as the “Masters of the Universe” syndrome – the belief that because you know the numbers, you know with certainty, almost bordering on arrogance, what needs be done and all will be well with world if only managers would do what the analysts tell them to do. This lack of humility on the part of analysts puts managers offside and typically leads to analytics being ignored. Managers are experts in context. Their experience has given them an understanding, often intuitive, of the impact of context. Analysts should respect this knowledge and tap into it. Ultimately the problem lies in treating social human beings who learn from experience as if they behave in a very deterministic manner similar to molecules. The methods that have been so successful in generating knowledge in the natural sciences are not easily transferable to the realm of human behaviour. Economics has sought to emulate the natural sciences in adopting a scientific approach to the empirical testing of economic theory. This has had an enormous impact, sometimes detrimental, on the mindset of data analysts given that a significant number of data analysts have a background in economics and econometrics (i.e. the application of statistical analysis to study of economic data).

So what are the implications if we as data analysts accept the critical importance of context? I would argue there are five inter-related implications:

Implication 1: The need to recognise that datasets and analytical models are always human-created “realisations” of the real world.

The “infinitiveness” of the decision context implies that datasets and analytical models are always partial and selective. There are no objective facts as such. Indeed the Latin root of the word “fact” is facere (“to make”). Facts are made. We frame the world, categorise it and measure it. Artists have always recognised that their art is a human interpretation of the world. The French impressionist painter, Paul Cezanne, described his paintings as “realisations” of the world. Scientists have tended to designate their models of the world as objective which tends to obscure their interpretive nature. Scientists interpret the world just as artists do, albeit with very different tools and techniques. Datasets and analytical models are the realisations of the world by data analysts.

Implication 2: All datasets and analytical models are de-contextualised abstractions.

As realisations, datasets and analytical models are necessarily selective, capturing only part of the decision situation. As such they are always abstractions from reality. The observations recorded in a dataset are de-contextualised in the sense that they are abstracted from the totality of the decision context.

Implication 3: Data analytics should seek to generalise from a sample rather that testing the validity of universal hypotheses.

There are no universal truths valid across all contexts. The disciplinary mindset of economics is quite the opposite. Economic behaviour is modelled as constrained optimisation by rational economic agents. Theoretical results are derived formally by mathematical analysis and their validity in specific contexts investigated empirically, in much the same way as natural science uses theory to hypothesise outcomes in laboratory experiments. Recognising the unique, “infinitive” and uncertain nature of the decision context leads to a very different mindset, one based on intellectual humility and the fallibility of human knowledge. We try to generalise from similar previous contexts to unknown, yet to occur, future contexts. These generalisations are, by their very nature, uncertain and fallible.

Implication 4: Given that every observation in a dataset is unique in its context, it is vital that exploratory data analysis investigates whether or not a dataset fulfils the similarity and variability requirements for valid analytical investigation.

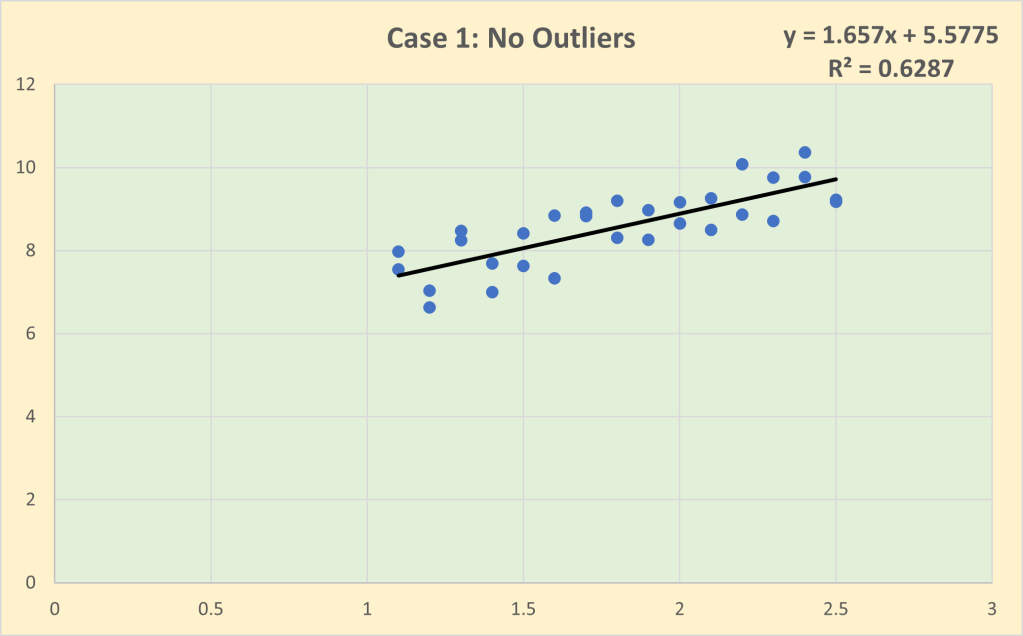

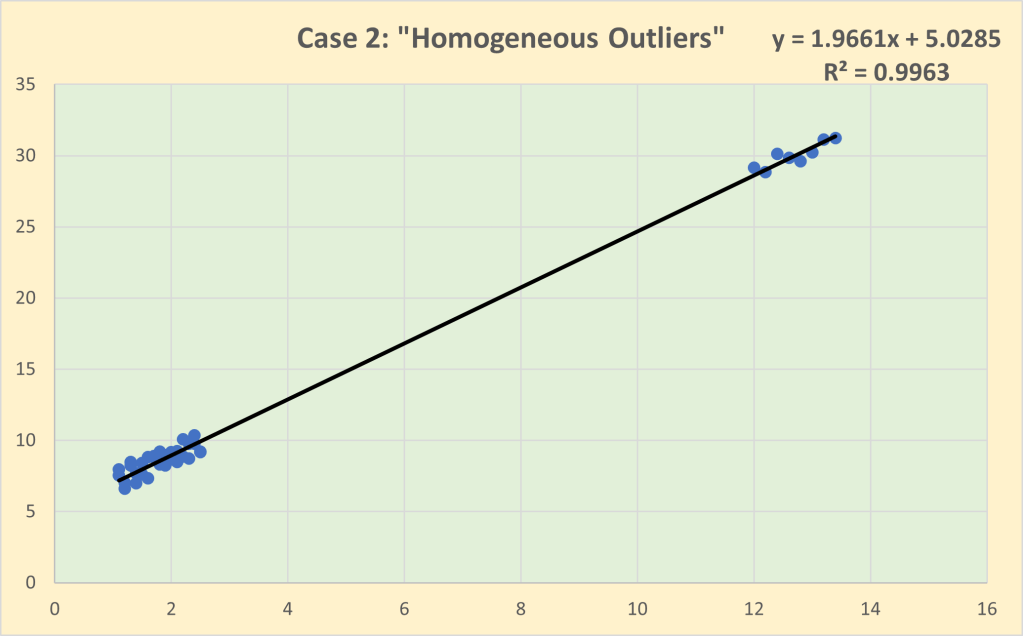

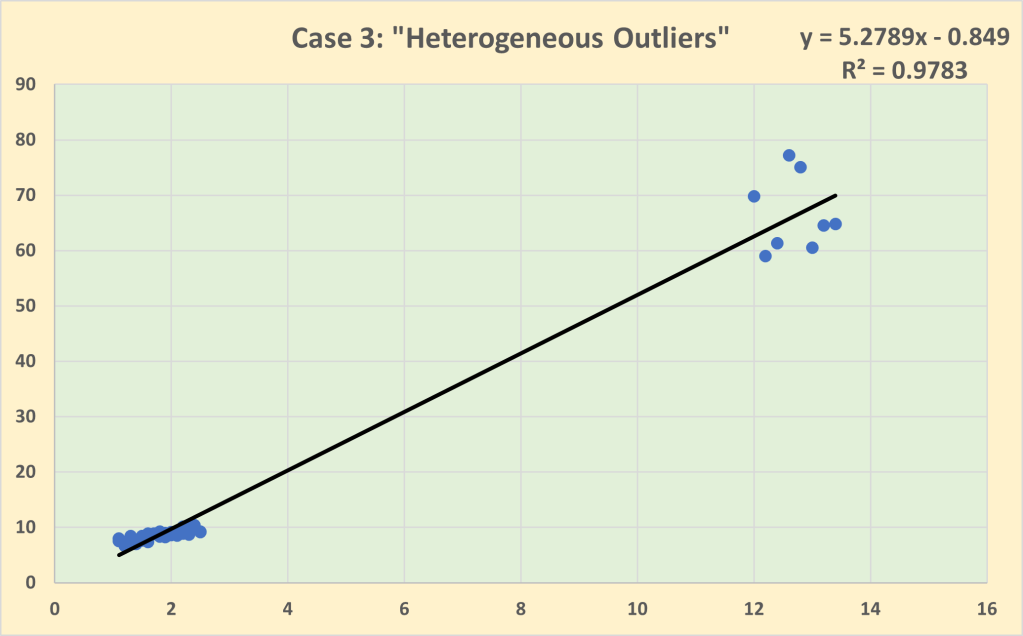

Every observation in a dataset is an abstraction from a unique decision context. One of the critical roles of the Exploration stage of the analytics process is to ensure that the decision contexts of each observation are sufficiently similar to be treated as a single collective (i.e. sample) to be analysed. The other side of the coin is checking the variability. There needs to be enough variability between the decision contexts so that the analyst can investigate which aspects of variability in the decision contexts are associated with the variability in the observed outcomes. But if the variability is excessive, this may call into question the degree of similarity and whether or not it is valid to assume that all of the observations have been generated by the same general behaviour process. Excessive variability (e.g. outliers) may represent different behavioural processes, requiring the dataset to be analysed as a set of sub-samples rather than as a single sample.

Implication 5: It can be misleading to consider analytical models as comprising dependent and independent variables.

Analytical models are typically described in statistics and econometrics as consisting of dependent and independent variables. This embodies a rather mechanistic view of the world in which the variation of observed outcomes (i.e. the dependent variable) is to be explained by the variation in the different aspects of the behavioural process as measured (or categorised) by the independent variables. But in reality these independent variables are never completely independent of each other. They share information (often known as “commonality”) to the extent that for each observation the so-called independent variables are extracted from the same context. I prefer to think of the variables in a dataset as situational variables – they attempt to capture the most relevant aspects of the unique real-world situations from which the data has been extracted but with no assumption that they are independent; indeed quite the opposite. And, given the specific practical purpose of the particular analytics project, one or more of these situational variables will be designated as outcome variables.

Read Other Related Posts