Executive Summary

- Data analytics is data analysis for practical purpose so the context is necessarily the uncertain, unfolding future

- Datasets consist of observations abstracted from relevant contexts and largely de-contextualised with only limited contextual information

- Decisions must ultimately involve re-contextualising the results of data analysis using the knowledge and experience of the decision makers who have an intuitive, holistic appreciation of the specific decision context

- Evidence of association between variables does not necessarily imply a causal relationship; causality is our interpretation and explanation of the association

- Communality (i.e. shared information across variables) is inevitable in all datasets, reflecting the influence of context

- There is always a “missing-variable” problem because datasets are always partial abstractions that simplify the real-world context of the data

As I argued in a previous post, “Analytics and Context” (9th Nov 2023), a deep appreciation of context is fundamental to data analytics. Indeed it is the importance of context that lay behind my use of the quote from the 19th Century Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, in the announcement of the latest set of posts on Winning With Analytics:

‘Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.’

Data analysis for the purpose of academic disciplinary research is motivated by the search for universality. Business disciplines such as economics, finance and organisational behaviour propose hypotheses about business behaviour and then test these hypotheses empirically. But the process of disciplinary hypothesis testing requires datasets in which the observations have been abstracted from individually unique contexts. Universality necessarily implies de-contextualising the data. Academic research is not about understanding the particular but rather it is about understanding the general. And the context is the past. We can only ever gather data about what has happened. As Kierkegaard so rightly said, ‘Life can only be understood backwards’.

Data analytics is data analysis for practical purpose so the context is necessarily the unfolding future. ‘Life must be lived forward.’ The dilemma for data analytics is that of life in general – uncertainty. There is no data for the future, just forecasts that ultimately assume in one way or another than the future will be like the past. Forecasts are extrapolations of varying degrees of sophistication, but extrapolations, nonetheless. So in providing actionable insights to guide the actions of decision makers, data analytics must always confront the uncertainty inherent in a world in constant flux. What this means in practical terms is that actionable insights derived from data analysis must be grounded in the particulars of the specific decision context. While data analysis whether for disciplinary or practical purposes always uses datasets consisting of observations abstracted from relevant contexts and largely de-contextualised, data analytics requires that the results of the data analysis are re-contextualised to take into account all of the relevant aspects of the specific decision context. Decisions must ultimately involve combining the results of data analysis with the knowledge and experience of the managers who have an intuitive, holistic appreciation of the specific decision context.

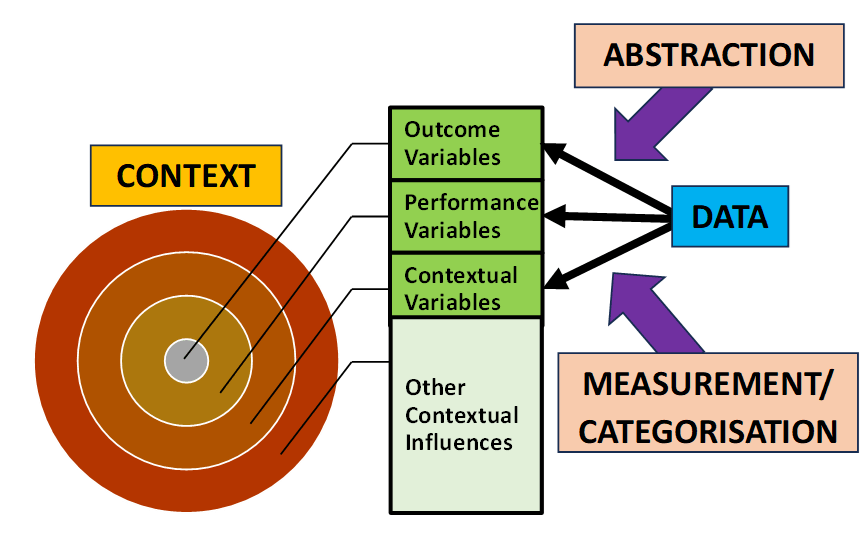

Effective data analytics requires an understanding of the relationship between context and data which I have summarised below in Figure 1. The purpose of data analytics is to assist managers to understand the variation in the performance of those processes for which they have responsibility. Typically the analytics project is initiated by a managerial perception of underperformance and the need to decide on some form of intervention to improve future performance. The dataset to be analysed consists of three types of variables:

- Outcome variables that categorise/measure the outcomes of the process under investigation;

- Performance variables that categorise/measure aspects of the activities that constitute the process under investigation; and

- Contextual variables that categorise/measure aspects of the wider context in which the process is operating

The dataset is an abstraction from reality (what I call a “realisation”) that provides only a partial representation of the outcome, performance and context of the process under investigation. This is what I meant by data always being de-contextualised to some extent. There will be a vast array of aspects of the process and its context that are excluded from the dataset but may in reality has some impact on the observed process outcomes (what I have labelled “Other Contextual Influences”).

Not only is the dataset dependent on the specific criteria used to determine the information to be abstracted from the real-world context, but it is also dependent on the specific categorisation and measurement systems applied to that information. Categorisation is the qualitative representation of differences in type between the individual observations of a multi-type variable. Measurement is the quantitative representation of the degree of variation between the individual observations of a single-type variable.

Figure 1: The Relationship Between Context and Data

When we use statistical tools to investigate datasets for evidence of relationships between variables, we must always remember that statistics can only ever provide evidence of association between variables in the sense of a consistent pattern in their joint variation. So, for example, when two measured variables are found to be positively associated, this means that there is a systematic tendency that as one of the variables changes, the other variable tends to change in the same direction. Association does not imply causality. At most association can provide evidence that is consistent with a causal relationship but never conclusive proof. Causality is our interpretation and explanation of the association. As we are taught in every introductory statistics class, statistical association between two variables, X and Y, can be consistent with one-way causality in either direction (X causing Y or Y causing X), two-way causality (X causing Y with a feedback loop from Y to X), “third-variable” causality i.e. the common causal effects of another variable, Z (Z causing both X and Y), or a spurious, non-causal relationship.

When we recognise that datasets are abstractions from the real world that have been largely been decontextualised, there are two critical implications for the statistical analysis of the data. First, as I have argued in my previous post, “Analytics and Context”, there is no such thing as an independent variable. All variables in a dataset necessarily display what is called “communality”, that is, shared information reflecting the influence of their common context. There will always be some degree of contextual association between variables which makes it difficult to isolate the shape and size of the direct relationship between two variables. Statisticians refer to an association between supposedly independent variables as the “multicollinearity” problem. It is not really a problem, but rather a characteristic of every dataset. Communality implies that all bivariate statistical tests are always subject to bias due to the exclusion of the influence of other variables and the wider context. In practical terms, communality requires that exploratory data analysis should always include an exploration of the degree of association between the performance and contextual variables to be used to model the variation in the outcome variables. Communality also raises the possibility of restructuring the information in any dataset to consolidate shared information in new constructed variables using factor analysis. (This will be the subject of a future post.)

The second critical implication for statistical analysis is that there is always a “missing-variable” problem because datasets are always partial abstractions that simplify the real-world context of the data. Again, just like the so-called multicollinearity problem, the missing-variable problem is not really a problem but rather an ever-present characteristic of any dataset. It is the third-variable problem writ large. Other contextual influences have an indeterminate impact on the outcome variables and are always missing variables from he dataset. Of course, the usual response is that they are merely random, non-systematic influences captured by the stochastic error term included in any statistical model. But these stochastic errors are assumed to be independent which effectively just assumes away the problem. Contextual influences by their very nature are not independent from the variables in the dataset.

To conclude, communality and uncertainty (i.e. context) are ever-present characteristics of life that we need to recognise and appreciate when evaluating the results of data analysis in order to generate context-specific actionable insights that are fit for purpose.

Other Related Posts

2 thoughts on “Putting Data in Context”